Let’s first turn to the obvious negatives. The Trump idea is an admission that he and pretty much everyone are unserious about addressing the housing unaffordability problem because too many powerful players benefit from it. The most obvious remedy is to build more middle/lower middle class residences in high cost areas. But right away, that runs hard into NIMBYism: all those well off with their tony houses don’t want the servant classes or even dull normals living nearby and possibly harming their property prices.

… the popular freely-refinancable (as in no prepayment penalty) 30 year fixed rate mortgage is a very unnatural product and is found in comparatively few advanced. economies. On paper, it puts the interest rate risk on the lender. If rates drop, borrowers refinance, taking the loan away from creditors just when taking the risk of longer-dated loans is paying off. There are many ways to better share the interest rate risk, such as barring refis for the first five to seven years of a mortgage, or having interest rates float subject to a floor and ceiling. I had that sort of product in the early 1980s and was very happy with it. You can pencil out what your worst-case mortgage costs might be and benefit with no expenditure of effort if interest rates fall.

So why is this supposedly borrower-favoring feature, of the “freely refinancable” fixed rate mortgage, actually not good for borrowers? Because that option is NOT free! Not only do borrowers pay fees when they refinanace, but lenders have succeeded in structuring refis so that roughly 2/3 of the economic benefit of the refi is captured by financiers, not by the homeowner.

A related bad feature of the refinancable 30 year mortgage is that it increases systemic risk. Mortgage guarantors Fannie and Freddie have to hedge the refi risk. That hedging is pro-cyclical on a systemically disrupting scale.

…

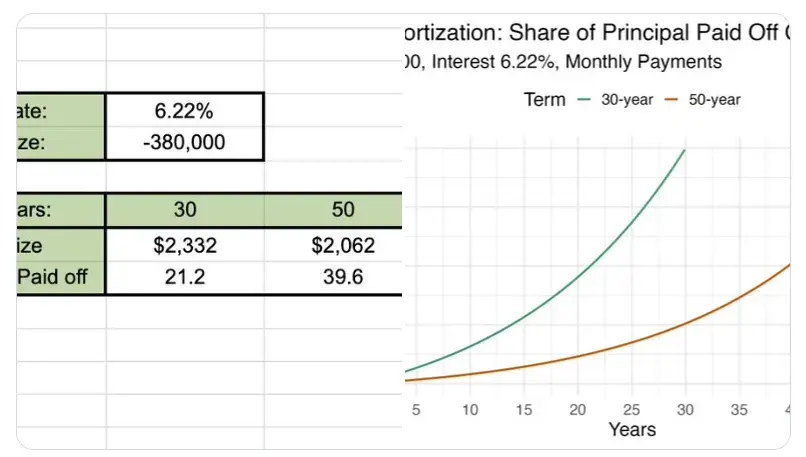

50 year mortgages, compared to a 30 year obligation have more of their payments over their life in interest. That means in a refi more total interest savings. That means even more in fee extraction by middlemen! More critically, it also means much greater pro-cyclical hedging action, and thus an even bigger increase in systemic risk, assuming that there actually was consumer receptivity to this bad idea…

Where I live, the opposite is true. Buying a new-build is like buying a Tesla: expect to spend the first few years fixing quality problems, with a residual risk that some can’t be fixed at all. And look at the neighborhood closely: it’s not unusual for new-bulid property to be far from useful infrastructure and services. In my Victorian neighborhood, there are shops, cafes, pubs, good schools, medical clinics. In far-flung new-build land, you might have to drive into my neighborhood to access any of those. And don’t bother taking the bus, because there are probably no bus routes either.

And all of the appliances and fixtures are “builder grade” which means they last 10 years and 1 week. Dripping faucets, fiddley light switches, stuck heat pump reversing valves, leaking water heaters.

It’s not like a new car where teething problems are resolved in the first year. You won’t know that your foundation is going to settle for several years, or that the vent boots on the roof leak a little bit until the sheathing rots enough for the drips to hit sheetrock.

That was actually a positive to me, I had it built in a semi-rural ex-urb. Nearest city is about 30 miles away.

Can’t speak for the quality of the build, other than it’s been four years, and the only issues are ones I expected (the floating floor is cheap and I’ll have to replace it in the next few years, and the exterior stain is peeling on trim bits and needs a touch up due to Colorado sun and weather extremes).